|

||

| Home | Login | Schedule | Pilot Store | 7-Day IFR | IFR Adventure | Trip Reports | Blog | Fun | Reviews | Weather | Articles | Links | Helicopter | Download | Bio | ||

Site MapSubscribePrivate Pilot Learn to Fly Instrument Pilot 7 day IFR Rating IFR Adventure Commercial Pilot Multi-Engine Pilot Human Factors/CRM Recurrent Training Ground Schools Articles Privacy Policy About Me Keyword:  |

Chapter 2. AERODYNAMICS OF POWERED FLIGHT  In any kind of flight (hovering, vertical, forward, sideward, or rearward), the total lift and thrust forces of a rotor are perpendicular to the tip-path plane or plane of rotation of the rotor (figure 9). The tip-path plane is the imaginary circular plane outlined by the rotor blade tips in making a cycle of rotation. Figure 9 (right) - The total lift-thrust force acts perpendicular to the rotor disc or tip-path plane.  Forces acting on the helicopter During any kind of horizontal or vertical flight, there are four forces acting on the helicopter - lift, thrust, weight, and drag. Lift is the force required to support the weight of the helicopter. Thrust is the force required to overcome the drag on the fuselage and other helicopter components. Hovering flight - During hovering flight in a no-wind condition, the tip-path plane is horizontal, that is, parallel to the ground. Lift and thrust act straight up; weight and drag act straight down. The sum of the lift and thrust forces must equal the sum of the weight and drag forces in order for the helicopter to hover. Vertical flight - During vertical flight in a no wind condition, the lift and thrust forces both act vertically upward. Weight and drag both act vertically downward. When lift and thrust equal weight and drag, the helicopter hovers; if lift and thrust are less than weight and drag, the helicopter descends vertically; if lift and thrust are greater than weight and drag, the helicopter rises vertically (figure 10 above).  Forward flight - For forward flight, the tip-path plane is tilted forward, thus tilting the total lift-thrust force forward from the vertical. This resultant lift-thrust force can be resolved into two components - lift acting vertically upward and thrust acting horizontally in the direction of flight. In addition to lift and thrust, there are weight, the downward acting force, and drag, the rearward acting or retarding force of inertia and wind resistance (figure 11 right). In straight-and-level unaccelerated forward flight, lift equals weight and thrust equals drag (straight-and-level flight is flight with a constant heading and at a constant altitude). If lift exceeds weight, the helicopter climbs; if the lift is less than weight, the helicopter descends. If thrust exceeds drag, the helicopter speeds up; if thrust is less than drag, it slows down. Sideward flight - In sideward flight, the tip-path plane is tilted sideward in the direction that flight is desired thus tilting the total lift-thrust vector sideward. In this case, the vertical or lift component is still straight up, weight straight down, but the horizontal or thrust component now acts sideward with drag acting to the opposite side (figure 11 to the right).  Rearward flight - For rearward flight, the tip-path

plane is tilted rearward tilting the lift-thrust vector rearward. The

thrust component is rearward and drag forward, just the opposite to

forward flight. The lift component is straight up and weight straight

down (figure 11b right). Rearward flight - For rearward flight, the tip-path

plane is tilted rearward tilting the lift-thrust vector rearward. The

thrust component is rearward and drag forward, just the opposite to

forward flight. The lift component is straight up and weight straight

down (figure 11b right). Figure 11b - Forces acting on the helicopter during rearward flight. Torque - Newton's third law of motion states, "To every action there is an equal and opposite reaction." As the main rotor of a helicopter turns in one direction, the fuselage tends to rotate in the opposite direction (figure 12). This tendency for the fuselage to rotate is called torque. Since torque effect on the fuselage is a direct result of engine power supplied to the main rotor, any change in engine power brings about a corresponding change in torque effect. The greater the engine power, the greater the torque effect. Since there is no engine power being supplied to the main rotor during autorotation, there is no torque reaction during autorotation.  Auxiliary rotor - The force that compensates for torque and keeps the fuselage from turning in the direction opposite to the main rotor is produced by means of an auxiliary rotor located on the end of the tail boom. This auxiliary rotor, generally referred to as a tail rotor, or antitorque rotor, produces thrust in the direction opposite to torque reaction developed by the main rotor (figure 12 right). Foot pedals in the cockpit permit the pilot to increase or decrease tail rotor thrust, as needed, to neutralize torque effect. Gyroscopic precession - The spinning main rotor of a helicopter acts like a gyroscope. As such, it has the properties of gyroscopic action, one of which is precession. Gyroscopic precession is the resultant action or deflection of a spinning object when a force is applied to this object. This action occurs approximately 90° in the direction of rotation from the point where the force is applied (figure 13). Through the use of this principle, the tip-path plane of the main rotor may be tilted from the horizontal.  The movement of the cyclic pitch control in a two-bladed

rotor system increases the angle of attack of one rotor blade with the

result that a greater lifting force is applied at this point in the

plane of rotation. This same control movement simultaneously decreases

the angle of attack of the other blade a like amount, thus decreasing

the lifting force applied at this point in the plane of rotation. The

blade with the increased angle of attack tends to rise; the blade with

the decreased angle of attack tends to lower. However, because of the

gyroscopic precession property, the blades do not rise or lower to

maximum deflection until a point approximately 90° later in the

plane of rotation. In the illustration (figure 14 below), the

retreating blade angle of attack is increased and the advancing blade

angle of attack is decreased resulting in a tipping forward of the

tip-path plane, since maximum deflection takes place 90° later when

the blades are at the rear and front respectively. The movement of the cyclic pitch control in a two-bladed

rotor system increases the angle of attack of one rotor blade with the

result that a greater lifting force is applied at this point in the

plane of rotation. This same control movement simultaneously decreases

the angle of attack of the other blade a like amount, thus decreasing

the lifting force applied at this point in the plane of rotation. The

blade with the increased angle of attack tends to rise; the blade with

the decreased angle of attack tends to lower. However, because of the

gyroscopic precession property, the blades do not rise or lower to

maximum deflection until a point approximately 90° later in the

plane of rotation. In the illustration (figure 14 below), the

retreating blade angle of attack is increased and the advancing blade

angle of attack is decreased resulting in a tipping forward of the

tip-path plane, since maximum deflection takes place 90° later when

the blades are at the rear and front respectively.  In a three-bladed rotor, the movement of the cyclic

pitch control changes the angle of attack of each blade an appropriate

amount so that the end result is the same - a tipping forward of the

tip-path plane when the maximum change in angle of attack is made as

each blade passes the same points at which the maximum increase and

decrease are made in the illustration (figure 14) for the two-bladed

rotor. As each blade passes the 90° position on the left, the

maximum increase in angle of attack occurs. As each blade passes the

90° position to the right, the maximum decrease in angle of attack

occurs. Maximum deflection takes place 90° later - maximum upward

deflection at the rear and maximum downward deflection at the front -

and the tip-path plane tips forward. Figure 14 (above) - Rotor

disc acts like a gyro. When a rotor blade pitch change is made, maximum

reactions occurs approximately 90° later in the direction of

rotation. In a three-bladed rotor, the movement of the cyclic

pitch control changes the angle of attack of each blade an appropriate

amount so that the end result is the same - a tipping forward of the

tip-path plane when the maximum change in angle of attack is made as

each blade passes the same points at which the maximum increase and

decrease are made in the illustration (figure 14) for the two-bladed

rotor. As each blade passes the 90° position on the left, the

maximum increase in angle of attack occurs. As each blade passes the

90° position to the right, the maximum decrease in angle of attack

occurs. Maximum deflection takes place 90° later - maximum upward

deflection at the rear and maximum downward deflection at the front -

and the tip-path plane tips forward. Figure 14 (above) - Rotor

disc acts like a gyro. When a rotor blade pitch change is made, maximum

reactions occurs approximately 90° later in the direction of

rotation.  Dissymmetry of lift - The area within the tip-path plane

of the main rotor is known as the disc area or rotor disc. When

hovering in still air, lift created by the rotor blades at all

corresponding positions around the rotor disc is equal. Dissymmetry of

lift is created by horizontal flight or by wind during hovering flight,

and is the difference in lift that exists between the advancing blade

half of the disc area and the retreating blade half. Dissymmetry of lift - The area within the tip-path plane

of the main rotor is known as the disc area or rotor disc. When

hovering in still air, lift created by the rotor blades at all

corresponding positions around the rotor disc is equal. Dissymmetry of

lift is created by horizontal flight or by wind during hovering flight,

and is the difference in lift that exists between the advancing blade

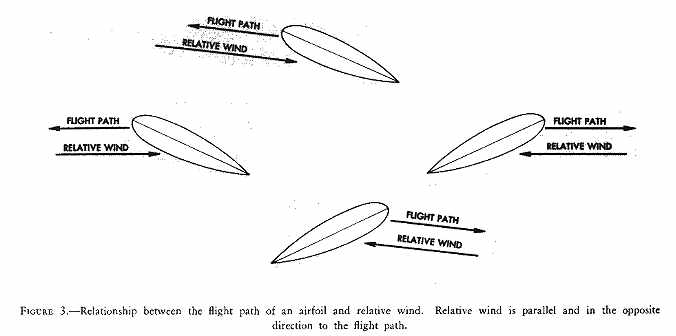

half of the disc area and the retreating blade half. At normal rotor operating RPM and zero airspeed, the rotating blade-tip speed of most helicopter main rotors is approximately 400 miles per hour. When hovering in a no-wind condition, the speed of the relative wind at the blade tips is the same throughout the tip-path plane (figure 15, right). The speed of the relative wind at any specific point along the rotor blade will be the same throughout the tip-path plane; however, the speed is reduced as this point moves closer to the rotor hub as indicated by the two inner circles. As the helicopter moves into forward flight, the relative wind moving over each rotor blade becomes a combination of the rotational speed of the rotor and the forward movement of the helicopter (figure 15a, below). At the 90° position on the right side, the advancing blade has the combined speed of the blade velocity plus the speed of the helicopter. At the 90° position on the left side, the retreating blade speed is the blade velocity less the speed of the helicopter. (In the illustration, the helicopter is assumed to have a forward airspeed of 100 miles per hour.) In other words, the relative windspeed is at a maximum at the 90° position on the right side and at a minimum at the 90° position on the left side.  Earlier in this handbook, the statement was made that for any given angle of attack, lift increases as the velocity of the airflow over the airfoil increases. It is apparent that the lift over the advancing blade half of the rotor disc will be greater than the lift over the retreating blade half during horizontal flight, or when hovering in a wind unless some compensation is made. It is equally apparent that the helicopter will roll to the left unless some compensation is made. The compensation made to equalize the lift over the two halves of the rotor disc is blade flapping and cyclic feathering. Blade flapping - In a three-bladed rotor system, the rotor blades are attached to the rotor hub by a horizontal hinge which permits the blades to move in a vertical plane, i.e., flap up or down, as they rotate (figure 16 below). In forward flight and assuming that the blade-pitch angle remains constant, the increased lift on the advancing blade will cause the blade to flap up decreasing the angle of attack because the relative wind will change from a horizontal direction to more of a downward direction. The decreased lift on the retreating blade will cause the blade to flap down increasing the angle of attack because the relative wind changes from a horizontal direction to more of an upward direction (figure 3 below). The combination of decreased angle of attack on the advancing blade and increased angle of attack on the retreating blade through blade flapping action tends to equalize the lift over the two halves of the rotor disc.  In a two-bladed system, the blades flap as a unit. As

the advancing blade flaps up due to the increased lift, the retreating

blade flaps down due to the decreased lift. The change in angle of

attack on each blade brought about by this flapping action tends to

equalize the lift over the two halves of the rotor disc. In a two-bladed system, the blades flap as a unit. As

the advancing blade flaps up due to the increased lift, the retreating

blade flaps down due to the decreased lift. The change in angle of

attack on each blade brought about by this flapping action tends to

equalize the lift over the two halves of the rotor disc.  The position of the cyclic pitch control in forward flight also causes a decrease in angle of attack on the advancing blade and an increase in angle of attack on the retreating blade. This, together with blade flapping, equalizes lift over the two halves of the rotor disc.  Coning - Coning is the upward bending of the blades

caused by the combined forces of lift and centrifugal force. Before

takeoff, the blades rotate in a plane nearly perpendicular to the rotor

mast, since centrifugal force is the major force acting on them (figure

17). Coning - Coning is the upward bending of the blades

caused by the combined forces of lift and centrifugal force. Before

takeoff, the blades rotate in a plane nearly perpendicular to the rotor

mast, since centrifugal force is the major force acting on them (figure

17). As a vertical takeoff is made, two major forces are acting at the same time - centrifugal force acting outward perpendicular to the rotor mast and lift acting upward and parallel to the mast. The result of these two forces is that the blades assume a conical path instead of remaining in the plane perpendicular to the mast (figure 17 above). Coning results in blade bending in a semirigid rotor; in an articulated rotor, the blades assume an upward angle through movement about the flapping hinges. Your Thoughts... |

|

| Home | Login | Schedule | Pilot Store | 7-Day IFR | IFR Adventure | Trip Reports | Blog | Fun | Reviews | Weather | Articles | Links | Helicopter | Download | Bio |

| All content is Copyright 2002-2010 by Darren Smith. All rights reserved. Subject to change without notice. This website is not a substitute for competent flight instruction. There are no representations or warranties of any kind made pertaining to this service/information and any warranty, express or implied, is excluded and disclaimed including but not limited to the implied warranties of merchantability and/or fitness for a particular purpose. Under no circumstances or theories of liability, including without limitation the negligence of any party, contract, warranty or strict liability in tort, shall the website creator/author or any of its affiliated or related organizations be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, consequential or punitive damages as a result of the use of, or the inability to use, any information provided through this service even if advised of the possibility of such damages. For more information about this website, including the privacy policy, see about this website. |